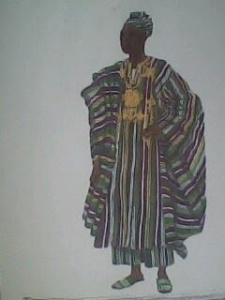

The sound of death is what wakes me up from my nap. It is a small mosquito that is dancing by my ears. My hands are pushing and slapping at it but it is trying to tell me something—about death. I do not want to listen because I know the person that has died. I rub my eyes groggily, until the blurry and hazy things in my vision stand still. I can see the angel of death standing by the net of our room. He’s dressed in a green and black pattered ankara, agbada. He even has a cap on. He has a big belly which pushes his agbada out—the way the bump of six month old pregnancy would push out a woman’s maternity gown. I know he is death because I have seen him before. I know he is death because he has a smug look on his face.

We are staring at each other—death and I. I have so many questions for him. I want to know why he came to my home next. Weren’t there other people he could have picked?

I was there the day he came to take the old man who owned the compound. It was just a year ago, and the old man had been seriously sick. We call the old man Daddy Ilaje. I saw him staring at the greenness of the landlord’s door, a smile playing around his lips. He saw me, twirled his moustache with his left hand, and with his right hand, motioned for me to come.

He whispered, slowly and charmingly in my ears, that he would be coming back for more. A few weeks later, the old woman who lived in one of the rooms in the backyard died. I did not see him that time, but I knew he was the one that picked her up—a woman who had not even been sick. She had just slipped on the wet ground and died. I was very angry because it was the old woman who used to tell me folktales. I was also angry because death was a glutton. I cried, but no one understood.

I’m determined not to cry now. The smell of death steals into me as I try to sit up, so I’m pushed back down, against the hard ground on which I have been sleeping. It smells of burnt soup mixed with the pungent smell of stale shit and urine.

My hands are beginning to itch. They itch the way they do when bedbugs slowly steal unto my skin and suck my blood. But there are no bumps now, just the itchiness, which I scratch relentlessly.

“Why won’t you please go away” I ask him in Yoruba, my small voice attempting to be loud “I don’t like you. I never would. Just leave my family alone”

He laughs. His laughter is even more sickening than the smell of death. I start towards him, more confidently as he starts to speak.

“I just wanted to tell you, I’m done with this compound dear” his voice is harsh, yet soothing. I’m near him. The angel of death has a bad odour distinct from the smell of death. He smells of garlic, cigarette and sweat—the way the louts at the bus garage normally smell. This odour mixes together with the smell of death that is painting itself on the walls of my home. “I just wanted to tell you, you won’t see me for many more years’ sweetheart”

I want to hit him, I clench my right fist, open the net and push my hands towards him—but it’s the curtain I’m pushing. There’s no one there but the green curtain of my home. This makes me angry and scared all at once. I look around—the boys are playing in the backyard. They would never believe me if I told them the angel of death has just left with sorrowful news

What if death was just joking, playing a fast one on me? What if I had only been imagining things?

I walk towards the compound’s front door, downcast. There’s a slight rumble in my stomach, and I know it’s not hunger. It is fear, dancing in me. I am wondering how I would survive. I swallow hard. I sit on the hard concrete ground. I do not care that I am still wearing my school uniform, I know that the moment my mother returns home, she would not notice it. Ordinarily, still having my uniform on, would have cost me a slap. She would be consumed in mourning the death of my father to even remember my existence.

My father. I wonder what sins he must have committed to be doomed with such a fate. Agony and pain—and a host of other evils, conspired against him. Though I’m barely six, I can tell this much. There were always so many worry lines on his face. He never smiled, and he was always looking ahead; even when he was sewing. My father loved to sew. He was a tailor, a very important one in the Bariga community even. But poverty was the order of our lives.

My father was always worrying even about the little things. He would worry about how I did not understand simple additions. He would worry about my brother, Kazeem, not doing well enough in the relay race at our inter-house sport. He would worry about his ex-wife, that she was the one orchestrating his ill lucks. He would worry about life—building a better home for us and removing the clutches of poverty that grabbed us. He would worry about my mother, the way she was boisterous, and always starting or ending arguments.

I feel like my mother is the cause of his death. Last week, she got into a fight with out late landlords wife. My father hadn’t been taken to the hospital on admission yet. He was still lying on the bed, nothing but a bag of bones, looking but not seeing, moving his lips, but not speaking. Insanity was working itself through him.

In the argument with our landlady, my mother had accused the landlady saying “We all know that you killed your husband.” That was the final straw of the argument. I couldn’t believe my mother would say that to an old nice lady and I dare say; she does have a heart of gold. The landlady, delving into her dialect—the egun dialect, spawned curses, all sorts of curses, at my mother. I saw curses rolling and dancing towards my door. It was then I first knew my father would be dying soon. Very soon.

And now he is gone. I wonder what life holds for my brothers and I, beyond today. My mother is just a cleaner, and as affordable as this “face-me-I-face-you” compound, is supposed to be, I am pretty sure she cannot afford it. I wonder if we would have to beg on the road, as the Fulani men and women do on Abeokuta Street. There are many of them there, and I wonder if they would accommodate us. I wonder if I would have to stop going to school—gladly even. I hate school. I hate the way I’m beaten every second for flimsy reasons. My teacher has wickedness running with her blood. She says the education we are getting is almost completely free, yet we are good for nothing. I listen to those words, every day, the koboko, hitting my skin, as if I am nothing but an animal. Hence, I have come to this conclusion; school is not right—at least for me. Maybe we would hawk. Bolatito might continue to his tailoring school. But Kazeem and I, might start selling plantain on the streets of Bariga. Of course, mother can do us a favour by marrying a second husband, a richer one, that can control her—that would be the ultimate plan.

If I had known that my life would head in this direction, I probably would have died at birth. I hate this life. I hate that people are saying my mother was the one killing my father. It is questionable and probably true, but I do not want them talking about it like it is their business.

My mother was always so lively during his illness—dressing well and plaiting beautiful hair styles. She was always complaining too: “I can’t go anywhere; you’re his daughters too, come look after him. I have places to go. He’s stressing me”

They only took him to the hospital a week ago, when he’d been sick for months, sickness; unknown.

My eyes flare up. The night is enveloping me, with a reassuring hug. Its darkness is soothing—but I know doom has only just arrived.

A cab screeches to a stop in the compound, and my mother comes out. Her hands are spread apart in sorrow. Then swiftly, she’s on the floor, rolling. My stepsisters are trying to carry her. The women from the compound rush towards her, weeping and trying to comfort her at once.

My mother is screaming.

“Baba Bolatito is dead, oko mi ti ku”

Tears are welling in my eyes. I wish there was something I could have done to stop the angel of death from visiting. I hate this scene— seeing my mother like that especially.

I bury my head on my laps, and ask for the angel of death to please come and take me away from all of this.

😦 😦 :(. Very well written, and very 😦

Mehn this story is just sad anyhow, beautifully written though. I hope its just a story sha and you are much much happier in real life.

😦