We call her aunty. We drag it, leaving out the a sound in the word and puncturing the on sound, so it ends up something like ontiiiiiii

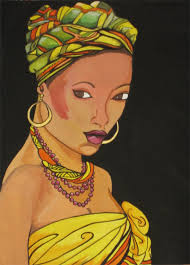

I only ever met aunty once—and that was during her wake keep, after her death. Her body lay in the parlor of my home in a brown and golden coffin, embalmed, unable to feel, but dressed exquisitely in a lace dress and royal beads, cotton wool adorning her nose. I remember the sheen in the darkness of her skin that is unlike the light skinned picture that has been on the wall of my home’s parlor, ever since I can remember.

I remember that if I got too close, I got a whiff of Aunty’s stench, mixed with the emergency perfume spray, my mother, her sister continuously sprayed, to prevent the heavy odor they said came with a corpse.

Before and after I met Aunty, I always wondered about her. I pondered on why she was just called aunty, without a name to follow, like my Mother’s other sisters; Aunty Bose, Aunty Bukky and Aunty Lara. I wondered why everybody, even Mother, who was a few years older than aunty, called her Aunty and nothing else but aunty. I wondered if she’d always been known as aunty.

I like to stare at Aunty’s picture that hangs on our wall. I like to wonder about the white and black picture of the beautiful young woman in the picture who is no more than thirteen. I stare at her low black hair. I stare at her white frock dress and flat ugly sandals, and then move back up to her face, to stare at the cat-like shape of her eyes and her wide smile that exposes milk teeth. I stare at the twinkle in her eyes thinking they are a reflection of the stars in the sky. She’s sitting on a wooden chair. I can’t discern the background of the picture but Mother says that, that’s what the front of our home used to look like in the early seventies. She would point at the sand that the wooden chair lays on and tell me about the soldier ants that matched through it in the rainy season. She would tell me to be thankful about so many things that have changed, mostly our interlogged ground. She would laugh heartily as she knit or cooked.

“My Mother and Aunty fought all the time because of that sand you know.” She would chuckle “never mind that girly picture, Aunty was never a girl. She was a tomboy. She loved the sand like it was her life. I don’t know what she did see in the sand. She’d pack sand in her hands and pretend she was going to build a house, mixing it with water like she said the builders did”

I loved to listen to stories about Aunty and this small home of mine which had been owned by my Grandmother but devolved to my Mother as the first child.

Maybe it was in the bits I captured from Mother whispers to her other sisters. Maybe it was in the way Mother shook her head after narrating one of Aunty’s nonsensical adventures. Maybe it was in the way Aunty’s name struck chords in me as strange. I don’t know but I soon realized even before her death that Aunty was a very sad woman. It could be a combination of the different reasons. Or instead, it could be that, in most of the grown up pictures I saw of Aunty, when my Mother and all my other aunties, had carved out families for themselves, Aunty stood distinctively out lacking that glimmer that I adored, her finger without a marriage ring.

I remember the day Aunty died. I recall the way my mother’s chest heaved; up and down, how her eyes danced all over the room. I remember how my mother didn’t cry. I remember how the other women, my aunties, were all silent. I had buried my nose into my Mothers laps, inhaling the Morgan’s Pomade and kitchen smell that her black skirt stank of, trying not to break their seemingly useful silence by crying.

I was chocked up by their silence and the smell of death that their black outfits carried with them. Camphor took prominence in the air, wafting around like the aroma of a well cooked meal, but the pungent smell of death stalled it. They had sweat on their forehead that stuck like droplets of water on a leaf after a rainy day. Someone raised a curtain, someone started to clap her hands, the rickety fan’s tune became persistent, but silence from the women prevailed.

It was Aunty Lara that first spoke. She told me to go outside and play with the rest of the children. I didn’t want to, so I looked up to my Mother for her final assent. She simply nodded her head and I was dismissed.

But I wouldn’t go far. I crouched by the verandah and listened for their voices. I knew they didn’t want me to hear whatever they had to say. Even now, I know I would probably never know Aunty’s full story because they didn’t want me to—apart from what the pictures seemed to tell about her sadness. But I stayed there, hanging on to the sound of their words, until Brother Michael came and caught me by the ear.

Aunty Bukky sighed and said, her voice husky that Aunty had no reason to kill herself.

My mother told the women they weren’t to dwell on that. She asked them, how were they to bury their beloved sister?

Aunty Bose raised her voice a little louder than necessary. She asked my Mother why she liked to avoid important issues. Aunty Bose is the youngest of the sisters. That day, I wondered only for a moment, what right she had to snap at my Mother like that, and why my Mother wouldn’t reply her.

I waited and waited for the conversation to go on but it never did to my hearing.

My curiosity grew even stronger after that day. I wanted to know everything about Aunty.

A while after the burial, I decided to take a bold step and went into my Mother’s vanilla smelling room, to find Aunty’s picture album. I finally found the object of concern after scrupulous searching. I pulled out the album that had been retrieved from Aunty’s house, after her death.

I started to leaf through, looking out mostly for Aunty. I noticed how Aunty was obviously the most beautiful of the sisters, and how her beauty waxed on as they grew older. I also noticed that a constant feature of Aunty’s pictures was that twinkle in her eyes, like the reflection of a glassy item was always in sight when she took pictures. But after a while, I noticed, Aunty’s face began to look gloomy, whatever the occasion. It seemed that a monster held the camera and compelled her to stand there, with a glamorous but fake smile adorning her face.

I also noticed that, after a while, the entries stopped. There were no pictures of her as a middle aged woman and I wondered why. I also wondered why she had never stopped by my home to see me since we all lived in the city of Lagos. She almost didn’t have an excuse.

There’s a strong conviction in my heart that Aunty was one of the unhappiest women ever. After all, she committed suicide. But I longed for Aunty. I longed to have that kind of beauty she had, and that kind of swagger she possessed. She stood tall, like one of the fashion models, with high cheek bones and hollows in their neck that mother called konga

Looking at the photos, I develop the story they seem to tell.

Aunty had a child out of wedlock but was too busy to take care of the child and so the child dies leaving Aunty really sad. In my story, my Mother condemned her for having a baby outside of wedlock and that’s why, Aunty never did come around to see me. They were estranged sisters who were once close.

The story appealed to my senses—and still somehow does, because the more I’ve thought about it, the more truth there is to it even though it doesn’t explain everything. I suppose the bulge of her stomach, in one of the photos, explains this line of reason. In that picture, where she looks or is pregnant, her eyes, smiled but didn’t have that luster. She doesn’t stand with any man either. There are no baby pictures that evidence a child. All the pictures dated after the supposed pregnancy date; show a sad but smiling Aunty.

And though everything about Aunty is still somewhat a mystery, I’m glad I have the pictures, to tell me a story.

Now that I reflect on the stories I have conjured of my Aunty, I realize the power of pictures.

Ope, this made me cry. There’s an honesty to this storytelling that is refreshing, thank you.

no, thank you, Fope. and thanks for enjoying this. 🙂

Hmmmn.

haha

You are going to blow this year!

amen

A picture they say, is worth a thousand words. A photo album owns a masterpiece of a story. A very nice one Ope.

Thank you Wale 🙂

This was really interesting.

thank you Tochukwu. 🙂

You are an amazing storyteller, I was hooked from the get-go. This made me really sad, I had an out of body experience – I felt like I was Aunty, and at the same time, I felt like I was the protagonist (you). I have a theory that the protagonist is the supposedly dead child of Aunty. But maybe that’s my inner Nollywood speaking.

Thank you so much. Glad you like it.

But you know, that’s an angle I didn’t look at (the protagonist being Auntys daughter) it makes perfect sense. It’s a perfect plot twist.

Nice story. You write well.

But erm…those pictures helped the girl to develop a story that’s not necessarily correct. They shush her and partly demystify Aunty.